On Thursday, January 9th we looked at the recent devastating floods in Valencia and discussed whether AI could have helped to predict them. First, we watched the following video which gives a chronology of the events leading up to the floods (The voice over is in Castellano, but auto-translated subtitles are available through Subtitled/Closed Captions settings on YouTube)

The article linked to below describes how the weather system which gave rise to the disaster formed. We used to call these storms “Gota Fria” (Cold Drop), but the correct meterological term is DANA (Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos). The article also describes how climate change is making these storms worse: Valencia floods: Our warming climate is making once-rare weather more common, and more destructive https://theconversation.com/valencia-floods-our-warming-climate-is-making-once-rare-weather-more-common-and-more-destructive-242798

Could the floods have been predicted?

We visited the Spanish Met office (AEMET) site and noted that they use two computer models for forecasts: Harmonie – Arome (a regional area model) and ECMWF (the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts). https://www.aemet.es/en/eltiempo/prediccion/modelosnumericos/harmonie_arome

MeteoAlarm created by the European Network of National Meteorological Services, is an Early Warning Dissemination System and displays live maps of weather alerts in Europe. It also gives descriptions of what the different weather alerts mean: Yellow, Amber and Red. https://meteoalarm.org/en/live/page/_legend#list

The following critique: Valencia’s flash floods: accurate predictions, failed prevention http://Valencia’s flash floods: accurate predictions, failed prevention notes: “On Friday, October 25th AEMET, the national meteorology agency, was already announcing a DANA with generalized rain across the entire Peninsula and heavy rains on the Mediterranean Coast. During the following days, the information became more precise regarding location (Valencia’s region and other south-eastern regions), intensity (torrential rains), and timing (on Tuesday and Wednesday). On the day of the flash floods, Tuesday October 29th at 7:36am, AEMET sent a first red alert in the area“

So, it seems the floods were predicted

The GNDR (Global Network of Civil Society Organisations for Disaster Reduction) provides a detailed account of communication and other failures in relation to the floods: The 2024 Spain Floods: Failures in Early Warning, Action, Coordination, and Localisation https://www.gndr.org/2024-spain-floods-early-warning-action-coordination-and-localisation/ They highlighted the need for stronger early warning systems and responsiveness to warnings. They noted that: “the Japanese embassy in Spain, acting on the same alert, notified its residents a day in advance, advising them to avoid the area or remain indoors.”

We discussed how the devolved structure of Spain’s political structure creates fragmented chains of responsibility contributing to the failure of timely alerts. Peter pointed out that this was not a problem unique to Spain, but that warnings about recent flooding in Germany suffered from similar failures. Peoples’ general lack of understanding about risk and politicians’ lack of technical knowledge also didn’t help.

Could AI have improved the forecast and assessed the severity of the event?

This article suggests that AI could make climate models better: Computer models are vital for studying everything from climate change to disease – here’s how AI could make them even better https://theconversation.com/computer-models-are-vital-for-studying-everything-from-climate-change-to-disease-heres-how-ai-could-make-them-even-better-244602 It mentions Google’s NeuralCGM which provides forecasts just as good as existing models and calculates them more quickly – however the Google model only describes the atmosphere – and floods are the result of many more factors e.g: the topography of the land, river basins, dryness of the ground, urban developments etc.

On the other hand, this article argues that AI can’t predict such events because of poor quality data and the irregular behaviour of weather events like the DANA : Why is AI unable to predict disasters like Spain’s flash flooding in time? https://english-elpais-com.cdn.ampproject.org/v/s/english.elpais.com/technology/2024-11-09/why-is-ai-unable-to-predict-disasters-like-spains-flash-flooding-in-time.html?

This stimulated vigorous discussion! We pointed out that AI needs to be trained on existing data and that weather data collected in the past, when the seasons were predictable, may be less relevant to today’s more chaotic weather conditions. Also, rare events are by definition rare, so there’s not much data on them. As regards the severity of an event and its consequences, it is obvious that confounding factors are of utmost importance: “It is not enough to know how much and where it will rain, but we also need to establish how that rain will turn into floods and which areas will be potentially affected,” also the lead time is important “No matter how accurate a forecasting is, its forecast does not have any value as information if it does not come soon enough,”

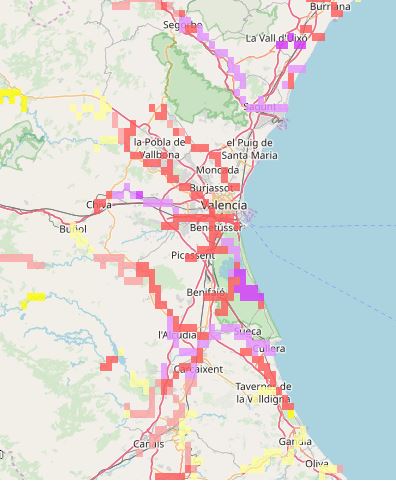

In this context we looked at the European Flood Emergency site: https://european-flood.emergency.copernicus.eu/efas_frontend/#/home This contains an enormous amount of data. Access to forecasts is restricted to authorised people, to prevent panic in the general populace. However historical data is freely available. This screenshot from the site shows that a serious risk of flooding in the disaster zones was predicted on the 27th – two days before the event.

There were also data on this site showing how social media posts relating to the flood had peaked on the 30th.

How should people be warned?

We discussed alert methods. There is an alert system for mobile phones, but it was used too late. It also has significant drawbacks: Not everyone has a mobile phone, if there are false alarms people will tend to ignore them, they may not be specific enough (and there are also technical problems including messages getting “stuck” in the relay system and being delayed. This issue was later highlighted in the California fire disaster). How about bringing back church bells and air-raid sirens? – they are still used in some countries! Why not tell everyone to tune into, or stream a particular TV or radio channel for details when they hear the impending disaster alarm?

The role of social media

Undoubtedly, WhatsApp messages were useful in spreading information during the disaster, however, there was also a lot of fake news. Some of which became viral conspiracy theories: TikTok and how DANA phenomenon hoaxes accumulate millions and millions of views without the social network stopping it https://maldita.es/malditobulo/20241112/hoaxes-dana-valencia-tiktok/

Our general conclusion: As always, the problem is not the technology, it’s the people.

Chris Betterton-Jones – Knowledge junkie